Editor’s note: In anticipation of my upcoming author presentation on Sept. 25 at the Sun Prairie Public Library, I’m publishing an excerpt from my first non-fiction book, “COLD,” released last fall. Any questions about the book or the presentation, comment below or send email to: kdamask@live.com. Thanks for reading!

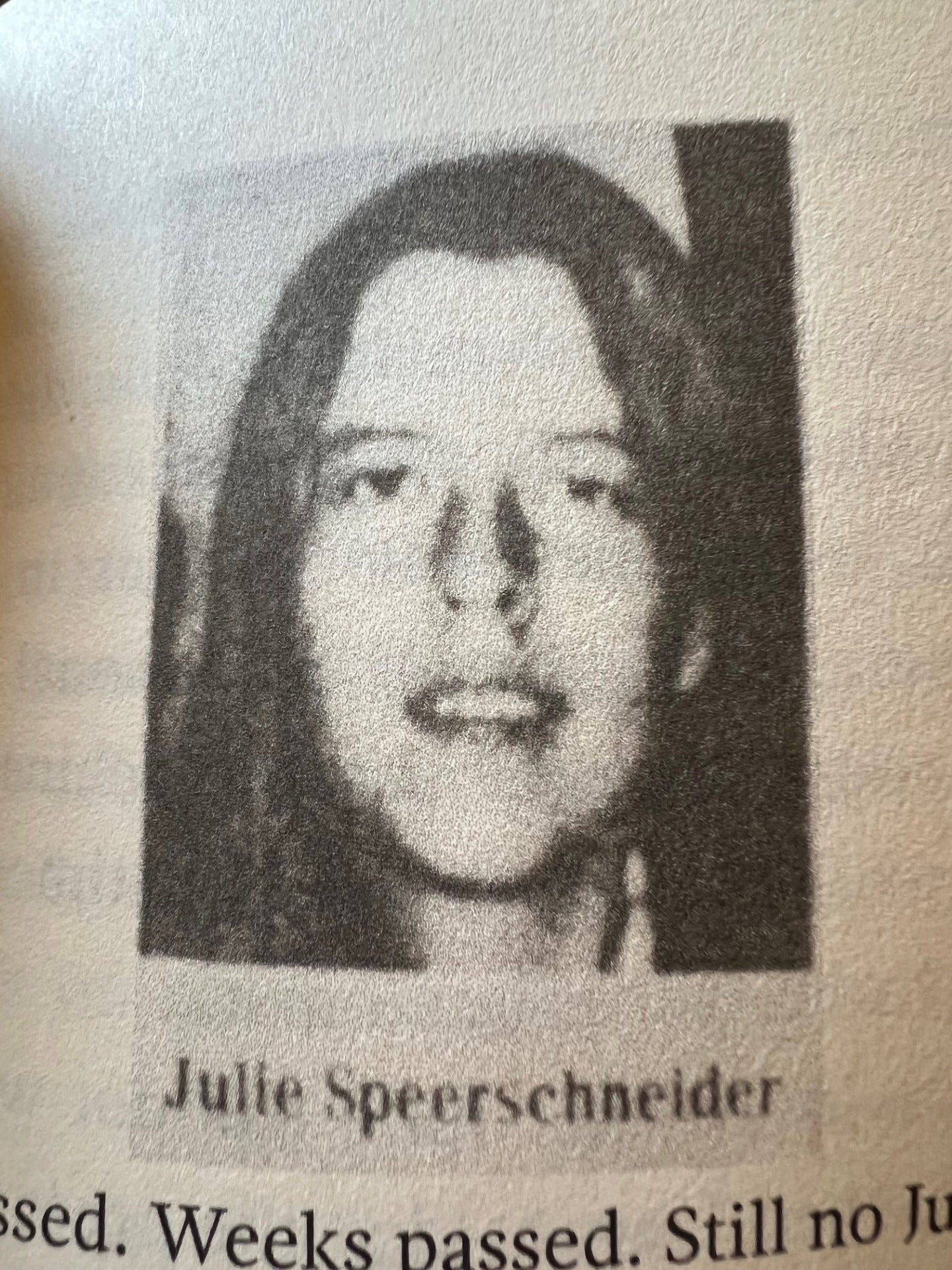

Julie Speerschneider was walking along Johnson Street, one block from her friend’s house when she vanished. It was March 27, 1979. A cold, foggy night.

Julie, a twenty-year-old Madison resident, had just hitched a ride to Johnson and figured she could just walk the short distance to her friend’s place. She had had fun tonight at the 602 Club near the UW-Madison campus, but it was nearing 9:00 p.m. It was a Tuesday night and she had to work the next morning.

Despite not attending college, she was the age of most college students. She enjoyed going out and having a good time, just like them. Unlike many students at UW, however, Julie was juggling three jobs. She had already started life at a time most women her age was still trying to figure life out. Julie was ready to wind down. She was excited to see her friend, catch up a little, and watch a movie. Probably call it a night after that. Get ready for another day.

Get ready for another day…

Julie never showed up at her friend’s house. The friend thought it was strange, since she had just talked to Julie. She had called her around 8:30 p.m. from the Memorial Union on campus.

“I’ll be there right away,” Julie replied.

But perhaps she had hitched a ride back home. It wouldn’t have been a big surprise. Julie was known to hitch rides around Madison, especially along Johnson Street.

Then Wednesday arrived. No Julie. Thursday came and went. No Julie. She had not shown up for the past three days at either of her jobs, at Tony’s Chop Suey restaurant, the Red Caboose Day Care Center, or the daycare on Baldwin Street. Since it had been more than forty-eight hours since anyone last saw her, she officially became a missing person.

On March 31, a small brief, headlined: “20-Year-Old Woman Reported Missing,” ran in the Capital Times. The three-paragraph article printed two numbers to call for anyone who knew anything about Julie’s disappearance. Her family offered a $500 reward for information.

The following day, the State Journal also ran a report on Julie with a bit more information. The paper ran a headshot photo of her. Julie had long brown hair, a soft, innocent smile, and friendly, welcoming eyes. The night she disappeared Julie was wearing blue jeans, boots, and a blue and gray-striped Mexican poncho. Julie was slightly underdressed considering it was only in the upper twenties with overcast skies when she left the bar to call her friend. Unseasonably cold for Madison in late March, but definitely not shocking early “spring” weather in Wisconsin.

Days passed. Weeks passed. Still no Julie.

By mid-May, after nearly two months since anyone last saw Julie, her family and friends started a search fund. The goal was to raise $8,000 by June 1 to hire a private investigator to search for their loved one. They also wanted to increase the $500 reward for information to her whereabouts.

On May 16, friends held a press conference announcing the fund at the Wil-Mar Neighborhood Center, 953 Jenifer Street, Madison. The announcement wasn’t far from where Julie lived with friends Gail Greenberg and Gary Rizzo at 524 S. Dickinson St. on the city’s East Side. Her friends asked the public to chip in what they could to the “Community Search for Julie,” set up through the First Federal Savings and Loan Association on State Street in Madison.

By May, police had pieced together some clues in Julie’s case. She hitchhiked a ride with a tall, young man. Investigators wanted to find that man.

Friends and family didn’t believe Julie simply up and left. That wasn’t like her. Not on her own, at least. Julie was not known to take trips without telling family and friends first.

On the night she went missing, Julie didn’t even have a purse with her. She carried no identification. No money had been taken from her bank account in the weeks after she left. No clothing or other personal items were taken from her room at the house on Dickinson. She had three jobs and while it was difficult at times to balance everything, she had never missed work.

“We are convinced that Julie has not walked off on her own,” her mother, Joan, said at the press conference.

If she had decided to run off with someone, she did a poor job of preparing for it.

The hitchhiking. Her mom was not pleased her daughter often accepted rides from strangers, but she understood why. Julie’s car had broken down earlier in the year. She had yet to find a replacement and depended on others to give her a lift.

Almost two months had passed with no leads. For Joan and David, Julie’s father, the feeling of not knowing tormented the Speerschneider’s every day. While local police pursued the case, the couple looked into other ways to find information on Julie. They talked to two psychics.

People can often be skeptical of the value of psychics. Do they really have the power to see what others don’t? Are they really well-intentioned, hoping to help people, or are they out to exploit? Prey on a vulnerable person’s emotions to make a few quick bucks?

By the spring of 1979, however, the Speerschneiders were desperate for any leads. Any piece of information. Any point of direction that could break open the case. While that could mean hearing something the family didn’t want to hear, it was worth a shot.

Psychics told Julie’s parents their daughter was dead. They would find her body buried, about thirteen miles northeast of Madison in the town of Burke. Detectives from Dane County and the city of Madison searched the area. Friends joined in the search. They found nothing. It was another frustrating day for all involved, but … were the psychics on to something? Julie’s mother believed they were.

“It looks that way,” Joan Speerschneider told reporters when asked if she believed the psychics premonitions.

Madison detective Mary Ostrander, also still working on the Julie Hall case, was the lead investigator on the Speerschneider case. Ostrander, a hard-driving, dedicated cop, was trying to pursue every lead she could, but there was little to go on. Jack Smith, another friend of Julie’s, wasn’t so fond of the police’s work on the case. “We have to work on the leads we have,” Smith was told. He thought police weren’t being aggressive enough in tracking down new information.

“We have genuine respect for law enforcement agencies,” Smith said. “But there is a serious flaw in the system that depends upon passive investigation.”

Smith said the public could have a hand in solving his friend’s case. They could support the fund or help search for Julie.

Police did find a man that said he thought he had picked up Julie and gave her ride on March 27. He said he drove Julie and another man to Johnson Street and let them out a block from her friend’s house. Did anyone see anything unusual? Did another motorist stop and offer Julie a ride after she had been let out?

“Someone knows what happened that night,” Joan Speerschneider said.

Through fundraising efforts, Julie’s friends and family were hoping to hire Sandra Sutherland, a private investigator from San Francisco. Sutherland led a P.I. agency in the Bay Area. She had a strong reputation. A Madison attorney told Julie’s friends Sutherland would be a good person to take on the case. She had an excellent track record in solving missing person cases, but she wouldn’t come cheap.

Police Turn to Hypnosis

Running out of options and with Julie still missing after several weeks, local police turned to an unconventional method—hypnosis.

It may have been a last-ditch effort to find a lead, but detectives were determined to try. They felt hypnosis could be used on witnesses to unlock a crucial piece of evidence in the case. While the technique wasn’t common in Madison or Dane County policing, at least back in the ‘70s, hypnosis can be used to help a witness recall certain events in detail. In some areas of the U.S., it was a common practice, especially for victims of violent crime. By tapping into the subconscious mind, victims can sometimes recall terrible events they’ve blocked out through “going under.”

Hypnosis can also be a flawed technique and not a credible procedure to solve crimes. Local police weren’t seriously thinking about using hypnosis on a regular basis, but in the Speerschneider case, they were downright desperate.

“There are times when we have cases with few leads and we have to use extraordinary methods,” Jack Heibel, detective captain for the Madison Police Department, told the Capital Times.

Investigators were hopeful they caught a break when they found the man who gave Julie a ride to Johnson Street. More like he found them. After learning about the missing twenty-year-old, he contacted the police and said he would like to help.

However, the young man’s memory was foggy. Several weeks had passed and he couldn’t recall for certain the young woman was Julie. He agreed to answer questions through hypnosis.

Through the help of Dr. Roger Severson, a clinical psychologist and UW-Madison professor, the man was put under hypnosis. Throughout the session, Detective Ostrander carefully probed the man with questions. Like a portal into the mind’s past, the trance brought him back to that night in Madison.

He remembered picking Julie up on the corner of Johnson and State. She was wearing a Mexican poncho. He also recalled another man hitching a ride. Small talk was made on the short drive. Julie didn’t appear to know the other passenger. The driver let them both out at the corner of Johnson and Brearly Street. They apparently walked away in opposite directions; Julie walked up Brearly and the man crossed Johnson.

To the man who gave Julie a lift, the pretty young woman with long brown hair and an easy-going smile was a fleeting memory. A brief interaction in a busy life of hundreds of interactions. Meeting Julie was a small moment in his life; no wonder the images were a bit hazy.

For Julie’s friends and family, however, who knew her well and loved spending time with her, Julie would never be forgotten.

On July 27, 1979, four months to the day Julie vanished, the Madison Theater Guild put on a production of “The Fantastics.” It was held at 8:00 p.m. at the McDaniels Auditorium inside the School Administration Building at 545 W. Dayton St. Proceeds from the play would go to the fund to help find Julie Speerschneider.

Months of detective work, fifteen psychics, hypnosis, a high-priced private investigator, and the never-ending efforts of those close to Julie, was still not enough. The case grew colder by the day.

Body Found Near River

Charles Byrd decided to go for a walk on the afternoon of April 18, 1981.

It was nice out, seasonable with temperatures hovering around sixty degrees. Byrd walked along the Yahara River, just north of Lake Kegonsa. The lake, part of a chain of four lakes in the Madison area, is southeast of the capital city, near McFarland. As the day crept along, clouds filled the mid-April sky. Rain wasn’t in the forecast, so Byrd didn’t think he would get caught in a downpour.

Byrd strolled through a thicket of woods that hugged the banks of the Yahara. For a sixteen-year-old kid, it was a nice way to kill time on a lazy Saturday. After months of the winter doldrums, it was finally spring in Wisconsin. Chores, homework, whatever awaited him back home could wait another day. It was a bit breezy, but hey, a fine sixty-degree day in April was nothing to scoff at. And this was a secluded area. Not many people walk down here. For a curious teenager, it was fun to explore.

As he approached the river, Byrd noticed something strange. It was barely visible, but something was definitely there. Could it be? No. It was. A skeleton was lying in the woods near the riverbank. Was it a deer? That’s certainly possible. But as Byrd carefully walked up to the remains, his heart sank. This was definitely not an animal.

I have this book and have read it-once. Time to reread it again. Kevin is a cool writer.