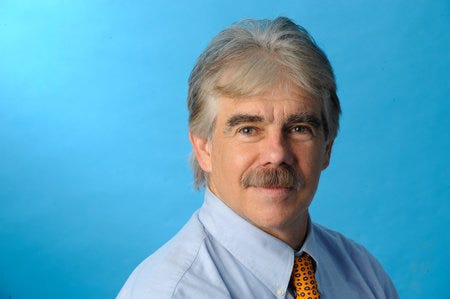

Talking about the 45th anniversary of the Miracle on Ice with journalist and author Wayne Coffey

The award-winning sportswriter reflects on 'The Boys of Winter,' writing books with athletes and the importance of listening to tell great stories

Wayne Coffey was feeling a tad miserable.

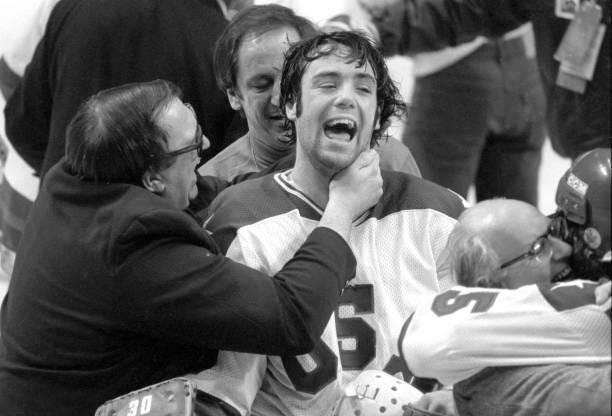

Here it was, Friday night, Feb. 22, 1980, and like millions of Americans, young Coffey was watching the greatest sports moment of the 20th Century unfold before his eyes. The U.S. hockey team, filled with wide-eyed college kids, were about to dethrone the mighty Soviet Union in an epic upset that still resonates more than four decades later, a moment of pure bliss.

But Coffey was busy keeping the Kleenex company in business. Watching the 1980 Olympic semifinal at his then-girlfriend’s house, Coffey kept one eye on the game and another on his girlfriend’s lovable dog, Fang. He was allergic to dogs.

“I must have gone through three boxes of Kleenex blowing my nose that night,” Coffey recalls.

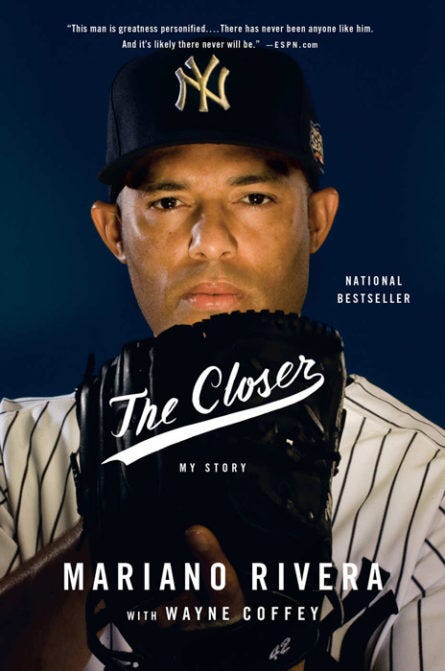

Twenty-five years later, Coffey would become the chief chronicler of the Miracle on Ice, penning “The Boys of Winter,” an excellent book diving into the many untold stories of the fabled 1980 Olympic hockey team. A former award-winning journalist with the New York Daily News, Coffey has gone on to write more than 30 (!) books, including autobiographies with Mariano Rivera, Carli Lloyd and other hall-of-fame athletes. He currently publishes Coffey Grounds, a Substack newsletter, where he constantly finds insightful, heartfelt stories to tell.

I recently caught up with Coffey over Zoom to chat about the 45th anniversary of the Miracle on Ice, how to find great stories, and the (mostly) pleasurable experience of writing books with athletes.

Kevin Damask: Do you still keep in touch with players from the 1980 Olympic hockey team?

Wayne Coffey: I do loosely. One of my favorite guys is Ken Morrow. Kenny is a wonderful guy and a very overlooked part of that team. He was the quintessential stay-at-home defenseman. He just did his job spectacularly well. He works for the New York Islanders now. I rode with him when he went up to Lake Placid to celebrate the 35th anniversary 10 years ago. I wrote a story about being on the road to Lake Placid with Ken Morrow. He still gets letters from fans about that game and responds to each one. Jim Craig, the goaltender, wrote the forward for the book and I’ll talk to him from time to time. Mark Johnson is one of my all-time favorites. I haven’t talked to him for a while, but he was great when I spoke to him for the book.

One of his close friends, Pete Giacomini, lives near Mark in Verona, Wisconsin. He was a former dairy industry executive. As you know, sometimes the best sources of information are not the person you’re talking to. It’s not Mark Johnson, not Jim Craig, it could be his wife or best friend. I talked to Pete for hours about Mark for the book and he gave some great insights. One of the things he told me was that Mark and his wife Leslie were trying to get rid of stuff and had a garage sale a long time ago. Pete was helping them price stuff and there were a pair of hockey gloves sitting on a bench, marked at $3. Pete asked, “What are those?” Mark said, “Oh, those are my gloves from Lake Placid.” Pete said, “Are you out of your fricken’ mind? You’re selling these for $3?! They should be hanging on a wall or handed down to your grandchildren.”

The beauty of that story is that Mark is such a humble guy. He just didn’t think his gloves mattered that much.

You never quite know where the hidden jewels will come from. I went up to the Iron Range in Minnesota where a few of the guys were from. A couple of them were from Eveleth, Minnesota where the U.S. Hockey Hall of Fame is. You go to a local bar, a coffeeshop in these small towns, everyone knows everyone. Before you know it, your notebook is stuffed with great stories.

The guys who were the biggest help for me are near and dear to my heart, like Buzz Schneider and Steve Janaszak, the backup goalie. He was the only athlete at the 1980 Winter Olympics that did not compete for one second in his sport. There were games when they were up by five or six goals and coach Herb Brooks never brought him in. Janaszak was his goalie at the University of Minnesota. In fact, he was an All-American who won a national championship for Brooks.

But he’s a great guy and was incredibly classy about the whole thing, saying, “I had the best seat in the house for the sports moment of the century.” Plus, he met his wife in Lake Placid. She was an interpreter.

KD: Why did you decide to write a book on the 1980 team? Obviously, there’s been a lot written about this historic moment, so why dig into it?

WC: There’s an interesting story behind that. I had done a book with an editor and publisher I really like, (Crown Publishers in New York) that was very different. I spent a year with a deaf women’s basketball team, Gallaudet University in Washington, D.C. The program is revered in the deaf community. I think it’s the world’s only four-year university for the deaf and hearing impaired. They had gone pretty deep in the NCAA Division III tournament, and I thought, I wonder if there’s a book here? There was. It was called “Winning Sounds Like This.” It’s a book chronicling their basketball season but it’s really about what it’s like living as a deaf person in America. I went down there, stayed in the dorms, and went on the road with the team. The coach even allowed me to sit on the bench. That book came out, and it did not sell 250,000 copies like “The Boys of Winter,” but it did get very good reviews and meant a lot to me. The editor wanted to do another book. He proposed the idea of writing a 1980 Olympic hockey team book.

At first, I was like, “Eh, I don’t really think so. Don’t we already know everything we need to know? It was an incredible moment, goosebump moment, but what more can we really say?” Well, I took my editor’s advice. The publisher bought the book and I’ve never been more wrong in my entire life.

It was a great moment, but we didn’t know the players’ stories and not much about Herb Brooks. He was a hockey lifer. The last player cut on the 1960 U.S. Olympic hockey team. He was actually in the initial team photo. But the general manager wanted Bill Cleary. Two brothers, Bob and Bill, both played for Harvard. They talked Bill into coming back even though he was already out of hockey, working on Wall Street. He finally said, “OK, I’ll do it, but under one condition – my brother is on the team, too.”

So, the brother got on the team, and they took Brooks off it. In fact, in the team photo, they just cut out Herb’s body and pasted Cleary’s photo over Herb. Talk about a dagger in the heart. Herb ends up watching the Squaw Valley Olympics, seeing the U.S. win the gold with his father in St. Paul. Brooks was a hard-driving guy. His players came to love him, but kind of like your best taskmaster teacher or coach, you don’t really have too many warm and fuzzy feelings at the time because they’re pushing you, but Brooks’ father was an incredible hard ass. The U.S. wins and Brooks’ father says to him, “I guess they picked the right guy.” Brutal.

There’s so much richness in the backstories of these guys. How they got there and what they put into it. The obstacles they overcame. Their life journeys.

I also made the decision to go to Moscow because no one had ever told the Russian side of the story. Well, I knew a Russian journalist from having covered past Olympics. This guy was probably the most famous sportswriter in the Soviet Union at the time, Seva Kukushkin and he knew Viktor Tikhonov well, the Soviet coach. He talked to Tikhonov and said, “Hey, this guy’s a good guy and he’s writing this book.” He hooked me up with Tikhonov and served as my interpreter. It was gold. No one had ever really shared their side of it, what it was like to come home afterwards. Sergei Makarov had a long career in the NHL and was a rising young star on the 1980 team. He told me after he got his silver medal, he dumped it in the garbage in the Olympic village. That’s what they thought of it.

One of the best interviews I did for “The Boys of Winter” was from Gary Smith, the head trainer. Trainers know everything. They work on these guys’ bodies, they’re there every single day. Gary had worked with Herb for several years in Minnesota and he trusted him explicitly. He was just phenomenal because he was there to take it all in. Brooks’ goalkeeping coach Warren Strelow was another guy who was just phenomenal.

He told me how he would be fast asleep in their hotel room when the team was on the road for their pre-Olympic tour and at 3 a.m. his phone would ring. It’s Herb Brooks on the other end. “Hey, I have a breakout play from our own end to tell you about.” Herb was just obsessed with hockey. But you don’t get those great stories if you don’t cast a wide net.

One of the things that’s so important, and this really rings true for younger journalists – the importance of listening. It seems like a no-brainer, but I’ve seen where it gets glossed over. I used to do it. But you just never know when a conversation might pivot in a different way. If someone says something and you’re really not tuned in, who knows what you’re going to miss. Just take it all in.

KD: I really loved learning the backstories of the players, even on guys I thought I knew well, like Mark Johnson, who’s a celebrity around Madison, Wisconsin, along with Bob Suter, who has unfortunately passed away.

WC: I actually went to see Bob at his ice rink. In fact, he was driving the Zamboni when I came there. There’s no substitute for being there. I wouldn’t have had that image of this guy with straw blond hair and stocky build driving the Zamboni.

One of the reasons why this game was so charged was that America was in a pretty dark place. We’re in a much darker place now, but back in 1980, inflation was terrible, gas prices were out of sight and there were gas shortages. President Carter talked about this malaise of the American spirit. Then the Soviets invaded Afghanistan. There was an impotence that people were feeling – like America was not what it used to be, then these college kids come together and beat the greatest hockey team ever assembled.

One of the most mind-blowing details of this game was that it was not on live TV. The puck in Lake Placid dropped at 5:07 Eastern time and ABC telecast started at 8:07. I did not know the score, the outcome – try getting away with that today. It’s crazy to think about how much the world has changed, the fact it was on tape delay. Lake Placid is so far north in New York State that you can pick up Canadian radio stations there and in Canada it was shown live.

KD: Do you remember what you were doing when the game aired?

WC: Oh yeah. For most of us there are a handful of times in our lives when moments are of such epic and historical significance that you remember exactly where you were when it happened. I can remember down to the square inch where I was on Nov. 22, 1963, when President Kennedy was shot. I was in Manor Plains School in Huntington, Long Island, in a corridor. I was in fourth grade and the announcement came over the loudspeaker. Same thing with Martin Luther King and Bobby Kennedy’s assassinations. But there’s not many times when you have that type of vivid recall over something that is joyful.

I was in the basement of my then-girlfriend’s house. I don’t even think she was watching the game, but she had a dog named Fang. Fang was a sweet dog but I was allergic to dogs. I spent that whole game going through like three boxes of Kleenex, just blowing my nose. But I can remember exactly where I was. It shows the enduring nature of the event.

And, when you put this moment into context, not only will something like this never happen again where a bunch of college kids go up against the best players of the world, but we’ll never see another Olympics in a place like Lake Placid. It’s a village of 2,000 people with one traffic light. For the first week of those Olympics, the town was in absolute gridlock, you couldn’t get anywhere. The bus transport system was a complete disaster. The governor declared a state of emergency and called for a whole fleet of busses to go up there. This was definitely small town Olympics.

Eric Heiden, the terrific speedskater, won his five gold medals on an outdoor oval in front of Lake Placid High School. If you visit Lake Placid today, you could skate on that oval. It is not fancy. It’s right next to Herb Brooks Arena. The Olympic village they built is now a minimum-security prison.

KD: I was really impressed how you tackled the format of the book. You had the play-by-play of the game and kept that going throughout the book, mixed in with these fantastic human-interest stories of the players. Was that something you thought of beforehand or as you started writing it?

KD: A friend suggested that idea. I was really struggling with the structure, and he told me about a book by writer and prolific author John McPhee. He’s in his nineties and still writing. One of the greatest non-fiction writers ever. He did a book, “Levels of the Game,” about a single tennis match between Arthur Ashe and Clark Graebner. They were the two top Americans at the time. One was an African American from Richmond, Virginia who was barred from playing on the public courts in the Jim Crow South and Graebner was an affluent kid from Shaker Heights, a largely Jewish community west of Cleveland.

McPhee starts that book with Ashe throwing the ball up in the air with the opening serve and on page two or three, he stops the tennis and talks about the slave ships that brought Ashe’s relatives over from Africa. So, I borrowed/stole that idea, and I think it worked. I wanted to build the narrative tension, so we get to the point where the focus is on the late Mark Pavelich. I talk about him growing up on the lake in Eveleth, Minnesota doing a lot of skating.

KD: You wonder what happened to some of the players that you don’t hear about as much. Where did they go in life after this seminal moment in 1980? You realize that for some of them, life doesn’t always turn out to be roses and cupcakes.

WC: Oh, for sure. Mark Wells was an undersized center and he had a really rough life and has since passed. Then you got Mike Eruzione, the captain, who’s turned his winning goal into his livelihood and has for 45 years. And his teammates are unmerciful: “That piece of shit shot that you took with the wobbly puck.” A junky goal but 45 years later, he’s still raising millions of dollars for Boston University, his alma mater. Everyone wants to play golf with Mike Eruzione. Herb Brooks used to have a great line, “Mike Eruzione believes in free speech, he’s just never given one.” Herb was a very funny guy, wicked-smart but could be as acerbic as they get.

Buzz Schneider was one of his fastest skaters. A jet on ice. One time, Herb told him, “Buzzy, you got million-dollar legs and a 10-cent brain.” Not a cuddly guy.

KD: You’ve co-written a few autobiographies with some major athletes like Mariano Rivera, R.A. Dickey, and Carli Lloyd. What are the pros and cons of writing a book with an athlete?

WC: The pros, it’s much easier. “The Boys of Winter” was a lot of work. For the Dickey and Rivera books, I wanted to see the places where they grew up. For Mariano, I had never been to Panama and he’s from this tiny fishing village. I wanted to go see this place. You go there and can’t believe anyone could get out of there. He had lived in a shack with dirt floors, no running water, no electricity. His father was a commercial fisherman, fished for sardines. I think Mariano was going to drop out of school and follow his father fishing for sardines.

So, you spend a lot of time taping interviews, transcribing. You still have to write the book and shape it, but you’re trying to do it in their voice, so it sounds like the subject. Any kind of writing is hard, but I would say it’s easier. In a lot of cases, payday can be better. R.A. was not a big name, so the advance was not huge, but he had an incredible story. With Mariano, he finished up a hall of fame career. The challenge was that he was finishing up his career and publishers want baseball books to come out at the start of spring training. So, his season ended like Nov. 1, and they wanted the manuscript by Dec. 31.

KD: Wow.

WC: Yeah, two months. It was insane. Finishing that was not pretty. I never could have done it if I had had kids your age. But sometimes there’s time constraints. With Mariano and Carli Lloyd, their agents got a deal with a publisher and then they went shopping for a writer. Whereas, with R.A. and a bunch of the other books, I had to write a proposal, and we had to go through the process. With Mariano, they had a big advance and out of that, they carved out money for the writer, me.

I think my heart is in the narrative non-fiction. You can do more things from a storytelling standpoint, but I’m not against bigger paydays either. (laughs)

KD: In telling their personal life stories, were these athletes pretty open with you?

WC: It really depends on the athlete but if you’re going to write a book, you need to open up. It’s so different from going into the Yankees or Mets clubhouse and barking a few questions at someone for a 750-word story. But R.A. was really open. Actually, everyone I worked with, Mariano too. He had a father who was really harsh. He was really against the whole baseball career. On the day of Mariano’s Yankee tryout, he was repairing fishing nets with his father. Then he had to take two busses like an hour and a half to get to Panama City. He was hungry so he stopped at a bodega to get a roll for a quarter. He shows up for the Yankee tryout. No glove. He had a mismatched uniform and a hole in one of his shoes. And he wasn’t even a pitcher, he was a shortstop. But they put him on the mound and he threw strike after strike and the Yankees saw something there. The Yankee scout came back to their house and they signed him for $2,000.

I asked him, “If I talked to you at 17, 18 years old and asked you about American baseball, what would you have told me?” He said, “Nothing. I didn’t know anything. I didn’t even know who Babe Ruth was, Henry Aaron, Jackie Robinson.” He was so naïve that he didn’t know he had to leave Panama to play for the Yankees. And Mariano is a smart guy, but he was so sheltered that he didn’t think he would have to leave Panama.

There’s plenty of people who love the idea of having a book but then they find out it’s a pretty labor-intensive process even when the athlete is not doing the writing. I wrote my last book with Briana Scurry, the hall of fame goaltender who broke all kinds of color barriers in women’s soccer. We spent scores of hours talking and she was completely open. She had a traumatic brain injury in the last game she played at a time when they didn’t know how debilitating these injuries can be. She had a severe concussion and never played another game. She ended up being physically and mentally disabled. Here she was, this world class athlete, and she could barely go into the kitchen and make a cup of coffee. She was fighting with insurance companies to get the care she needed. She was on the brink of suicide, standing next to a waterfall.

R.A. was sexually abused by both a male and a female as a kid and he never shared that with anyone. He really sabotaged his baseball career in many ways because of the shame he felt. He was so open that I spent hours talking to his therapist with his permission and I learned so much about this man and what he went through. If you want a good book, it’s got to be a deep dive.

With the right approach, listening skills and basic human sensitivity, it can result in a tremendous piece but can also be cathartic for the person who lives through this trauma.

KD: What are you currently working on? You have a great Substack, Coffey Grounds, but any book projects in the works?

WC: I’ve had a couple of book projects that looked to be on the runway about to take off and didn’t. I was actually going to work on one with Damar Hamlin, the Buffalo Bills player who nearly lost his life on Monday Night Football, but that ended up not coming to fruition. In the meantime, I’m doing my Substack, a few freelance pieces, and still waiting for a book idea that wins my heart.

My favorite kind of subjects are the ones that far-afield from the mainstream. If Patrick Mahomes’ agent called and said, “Hey, we’d like you to write his book,” I would be on the next plane to Kansas City, but I kind of love the stories that are untold. I’m sure that’s the satisfaction you get from writing about veterans. They’re new and powerful, and can be painful, but are untold. That’s why I loved the Gallaudet book because it was wonderful and fresh.

Wow, this was outstanding. I want to send this to every student journalist in the country.

Thanks for taking the time to talk with me, Kevin. I enjoyed your Kronicle.