Talking sports and writing with New York Times best-selling author Andrew Maraniss

Andrew Maraniss caught the bug for journalism and writing at an early age. It’s easy to see why. His grandfather, Elliott Maraniss, was editor of the Capital Times newspaper in Madison, Wisconsin and his grandmother, Mary Maraniss, edited books for the University of Wisconsin Press. His father, David Maraniss, is a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and has written some of the most famous sports and political biographies to grace the shelves, covering the likes of Vince Lombardi to Barack Obama to Jim Thorpe.

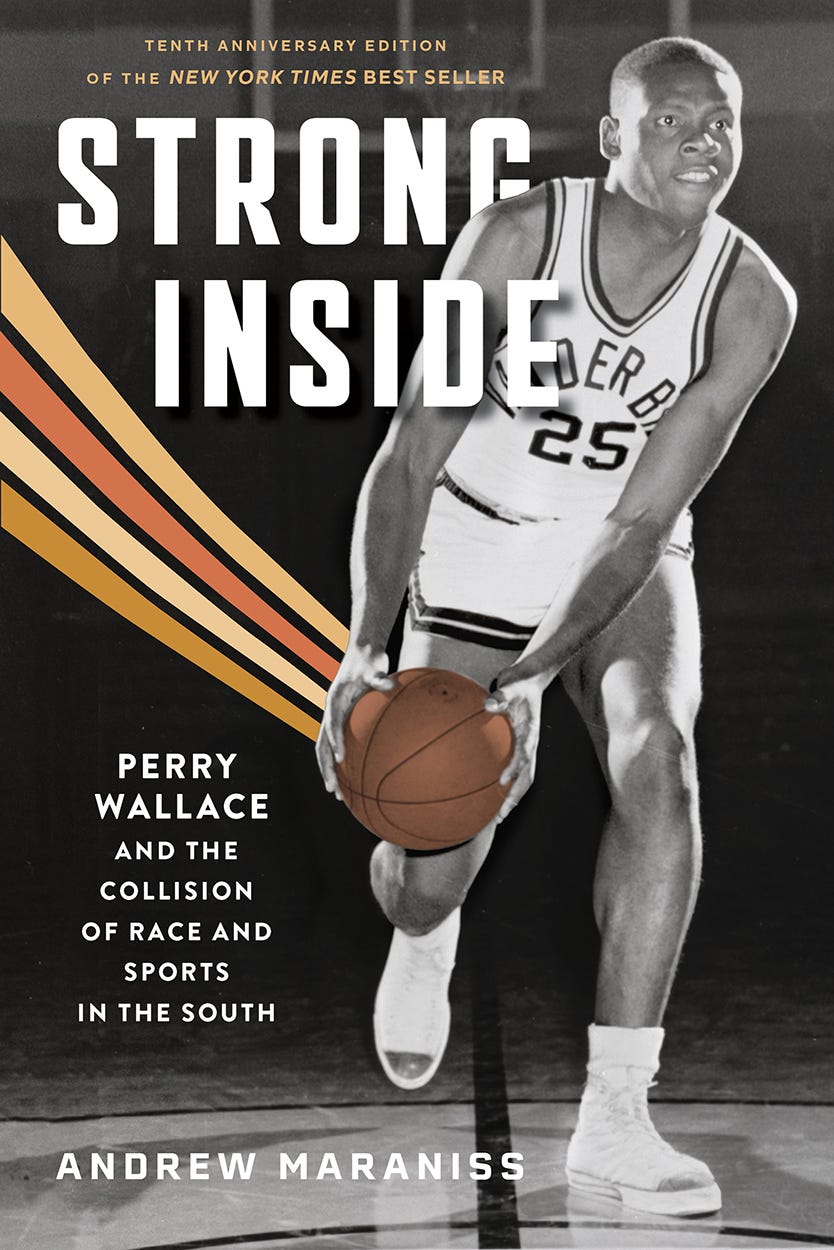

In the past decade, Andrew has found his own literary niche, penning several books on the intersection of sports and societal issues. His debut book, “Strong Inside,” follows Perry Wallace, the first Black college basketball player to hit the Southeastern Conference courts in the late 1960s.

Maraniss is releasing a special updated 10th anniversary edition of “Strong Inside” on March 5, along with two new books for young readers about basketball stars LeBron James and Maya Moore. In a recent Zoom interview, we talked about “Strong Inside,” the importance of keeping books on racial history and civil rights in schools, and one of Maraniss’ deepest passions – the Milwaukee Brewers.

Q: You’re a big Milwaukee Brewers fan. Do you have a favorite memory from watching the Brew Crew?

A: I was 12 years old when the Brewers went to the World Series in 1982. Prime age for being a baseball fan. That was probably the most intense baseball season of my life. I cried when Cecil Cooper got that hit against the (California) Angels in the ALCS, with happiness, then cried with sadness when Gorman Thomas struck out to end Game 7 of the World Series against the Cardinals.

We lived in Washington, D.C., so my dad and I would go up to Baltimore every time the Brewers would play the Orioles. The end of that ’82 season came down to that series in Baltimore, where they had to win just one game in a four-game series to clinch the AL East title. Well, we got tickets to the first three games, so we saw the Brewers lose three times and didn’t have tickets on that Sunday to see them win it. I remember that vividly.

The year before, in ’81, baseball went on strike, so they had a first-half division winner and a second-half division winner facing off in the AL East, so the Brewers played the Yankees in the playoffs. That was my first time in New York. My dad and I took a train up to New York and we went to each of those games at Yankee Stadium. For an 11-year-old kid, it was this eye-opening trip to the big city. Yankee fans were burning Brewers hats. … At one point, a fan jumped out of the stands and attacked the third base umpire with a blackjack. The Brewers won the first two games of that series, which was awesome. The family lore is that I packed my own suitcase for that trip, and I didn’t bring anything except for plastic ice cream baseball helmets, so the only thing I had to wear were the clothes I wore on the ride up there.

When I would visit my grandparents in Milwaukee every summer, they would always ask, “What do you want to do while you’re in town?” and all I ever wanted to do was go to a Brewers game. My grandmother took me four days in a row to County Stadium. I was a pen pal to Ben Barkin, one of the minority owners of the team. I would write him letters every offseason predicting what their starting lineup would be, what their stats would be. I had everybody hitting 40 home runs with 120 RBIs. He would write back and one time I got a letter from Harry Dalton, the general manager. I would get Christmas cards from the Brewers. It was the best. My whole identity was tied up in that team.

My dad and I made a pact that if Paul Molitor gets inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame, we’d go to Cooperstown, and we did.

Q: That must have been fun to share those experiences with your dad.

A: For sure. Now with my kids, I have a daughter who’s 13 and a son who’s 10. Our thing is going to all the Major League ballparks. So far, we’ve been to 21 stadiums, so we only have nine left before they go off to college. It’s been a fun way to see the country.

Q: Speaking of baseball, early in your career, you served as the media relations manager for the Tampa Bay (Devil) Rays during their first season. What was that like?

A: Yes, back in ’98. I had been the sports information director for the Vanderbilt men’s basketball team before that, from ’92-’97. That was my first job out of school. I was applying for jobs with every Major League team when I was a student in college and when I was working as SID. I saved all the rejection letters. I thought it was cool because they had the logos printed above the letterhead. Rick Vaughn was the head communications person for the Rays. He was looking for somebody who came from a college background that he could train in how he wanted to do things. I was lucky in that I got a job there in their first season.

Q: Wade Boggs was on that team, right?

A: Yeah, the best players were Boggs, Fred McGriff, Roberto Hernandez, Wilson Alvarez, Kevin Stocker, Miguel Cairo. The highlight for me was the last weekend of that season. I had told Rick and Larry Rothschild, the manager, that I was going to move back to Nashville after the season. Larry gave me the best going away present ever. The team’s last road trip was to Yankee Stadium, and he let me take batting practice there. Frank Howard, who was a coach on the ’82 Brewers, was the bench coach for the Rays that year, and threw batting practice to me. Then before the last game, I got to go on the field. You know how the starting pitcher and the pitching coach will walk across the outfield to the bullpen to warm up before the game? Well, Larry let me do that with them. I remember the fans harassing the starting pitcher. I don’t remember who it was, but I remember they were yelling at me too. It was a lot of fun.

Q: It’s been 10 years since your first book, “Strong Inside,” came out and you’re releasing an updated version. What will that feature?

A: The new pieces of the book will be a forward that’s written by Lou Moore, a professor at Grand Valley State and Derrick White, a professor at the University of Kentucky, two of the leading scholars on sports and race. I wrote a new epilogue that updates Perry Wallace’s story from the time the book came out in 2014 until the time he passed away and even to the present day. It’s got a new cover, forward and epilogue. Hopefully there will be some new readers. This field of society and sports has grown, whether at colleges or high schools, so there’s a new generation that would be interested in this book.

Q: As an author, picking a great topic for your first book can be nerve-racking. What attracted you to Perry Wallace’s story?

A: It goes back to when I was 19 and a student at Vanderbilt. I had to come to college on a sports writing scholarship named after Grantland Rice and Fred Russell, two well-known early 20th century sportswriters. I had been the sports editor at my high school newspaper in Austin, Texas, so I applied for the scholarship, was lucky enough to win it and that’s what brought me here. I came to Vanderbilt knowing that sports and writing were my things. During my sophomore year, in 1989, I was taking a Black history course and just coincidentally, Perry Wallace was invited back to campus to be honored, as the Jackie Robinson figure of the SEC. I read an article about him because I really hadn’t heard of him before and didn’t know much about Vanderbilt or SEC history. I felt he would be an ideal subject for the Black history course I was taking. I was concerned that my professor, Dr. Jones, was going to say, “We don’t write about basketball in college. That’s not a serious enough topic.” But she said, “If that’s what you want to do, go for it.”

I called Perry out of the blue. He was a law professor in Baltimore. He was very patient and kind. I talked to him for two hours. That experience of writing about him and learning from his experience and what it took to be a pioneer was the most interesting thing I did in college. But I didn’t have any notions of writing books back then. I graduated, got along with my career, got married … but I kept thinking about Perry Wallace. One day I was in my future father-in-law’s kitchen, and I said, “You know, I want to write a book.” He said, “What about?” I said, “Well, I don’t know. (laughs).” He said, “Well, what about Perry Wallace? You’re always talking about him.” I was like Oh, of course that’s what I should do. I quickly got on Google to make sure there wasn’t already a book about him and there wasn’t.

I emailed Perry and wrote, “I don’t know if you remember me, but 17 years ago I wrote a paper about you when I was in college, and I’m interested in writing a biography.” Of course, when you’re writing a biography, you don’t have to ask for your subject’s permission, but I wanted to make sure that he’d do interviews and be cool with the idea. He said, “Go for it.”

I really didn’t have a concept of how long it would take to write a book. Like most authors it’s not your full-time job. I ended up spending eight years on it; four years of research and four years of writing, this was without an agent or a publisher. I faced what a lot of first-time authors face: how do you find an agent or a publisher when you haven’t written a book yet? I ended up connecting with Vanderbilt University Press in Nashville. I don’t know if anyone really had any expectations for how it would do but it did surprisingly well. It was a big surprise to me and to Vanderbilt Press and I was most happy about that because I felt like Perry Wallace is one of the smartest people I’ve ever met, one of the most courageous I’ve ever met. His story is so much more than just basketball. We often celebrate pioneers but don’t often celebrate the tool of pioneering. He was such a wise person. He could explain that. He could look at his life from the outside and put that into perspective and share so much about race and racism and what it was like being a teenager during the Civil Rights Movement in the South. Growing up in segregation and not so much the fears of pioneering, like stepping on a basketball court in Starkville, Mississippi in 1968, but also the danger of that and the isolation he felt on his own campus. His ability to explain what that felt like elevated his story to another level.

Q: It seems like more stories like Mr. Wallace’s have finally been coming to light in recent years. Why is it so important for younger generations to hear or read about these stories?

A: Well, I’ve also done a young readers adaptation of “Strong Inside,” so I visit a lot of schools and talk to a lot of young people about these stories. For one thing, it’s not ancient history. A lot of these pioneers are still living. I think sports is an accessible way to talk about important social issues. It’s not necessarily intimidating for a young person to pick up a book with a basketball player on the cover, and if they read that book, they’re going to learn something about civil rights, racism. Maybe the story took place in the past, but it’s still incredibly relevant today. Sadly, increasingly relevant today.

At Vanderbilt, they ask/require incoming students to read the same book and then they come together in small groups and discuss the book. For two years in a row, they were asked to read “Strong Inside,” so here were kids who had not even taken a class yet at their new college that were learning about a previous student that didn’t have a great experience here and about racism on this campus in the 1960s. I think it's an effective way to learn about someone’s experience in the past and then apply that to the present. How can we make sure that this is a campus that’s welcoming, and students don’t have this type of experience? That’s another reason learning about these pioneers is important because it can spark those discussions.

Q: You’ve been quite vocal on social media about your disdain with the crazy book banning initiatives we’re seeing across the country in schools and with states limiting what types of history teachers can present to their students. History is important, especially lessons on civil rights and racism, and it feels like kids are really missing out.

A: Oh, yeah, tremendously. It’s outrageous what’s happening in some communities with book bans, threats to certain books, challenges, questioning and threatening librarians and teachers … preventing the truth from being taught or learned and just the choice of a student to walk into a library and decide for themselves what they want to read. Or parents saying because they don’t feel like this book is appropriate for their kid that it’s not appropriate for any kid. I think these efforts are tied to other things happening, like threats on voting rights or attacks on democracy itself, it’s all connected.

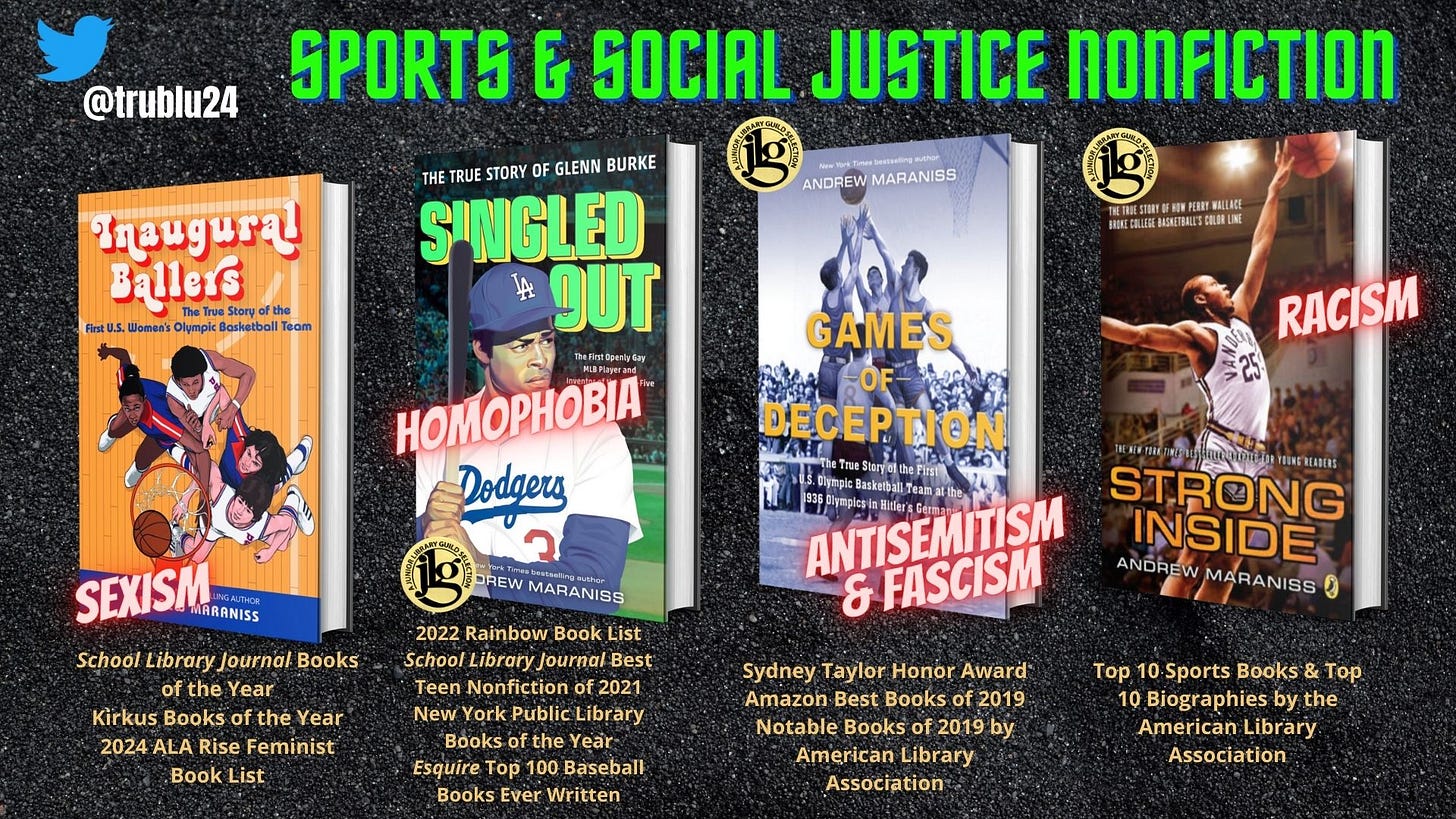

It’s all the more reason for me to write these books about sports and social issues. First of all, they’re true stories that I’m writing, there’s no reason why they shouldn’t be told. Secondly, they’re inspiring to young people. For some kids, they can see themselves and their own experience reflected in these stories and take something from it, like how to navigate these situations. For other kids, maybe it creates some empathy and the ability to put themselves in other people’s shoes and to become aligned with others in their school environment or community that are facing these types of problems.

Q: What’s wrong with kids learning a little empathy? It can be easy for someone to judge another person of a different racial background or different societal experience, but they haven’t walked a mile in their shoes. To not give kids a chance to learn other people’s stories blows my mind.

A: The thing is when I meet with kids in schools, they have such a strong sense of what’s fair or not or what’s just or not. It’s plain as day for them to see how Perry Wallace was treated or Glenn Burke in my book “Singled Out.” He was run out of baseball because he was gay. The women I wrote about in “Inaugural Ballers” who were playing basketball at a time when young women were told they shouldn’t sweat, they shouldn’t have muscles, they shouldn’t compete. Kids are like, “What are you talking about?” They can see that so clearly. That’s what threatens some people. They don’t want them to see those types of things or to act in some ways that would solve those similar problems today.

Q: You come from a rich family background in journalism and writing. What were the key aspects you learned from them to apply to your own career?

A: Without even knowing it, just being surrounded by people that were writers was influential to me, whether it was visiting my grandparents in the summer and knowing my grandfather was an editor and those were they types of people he hung out with or would come visit him. There were always piles of newspapers at my grandparents’ house, tons of books. Reading was always happening in their house. It wasn’t unusual for everyone to be sitting on the couch, reading a book, reading the paper with not much talking going on.

I tagged around with my dad a lot when he was a reporter. My parents were only 20 years old when I was born, so I was kind of in the latchkey generation, there weren’t lots of planned afterschool activities. I would just go to his office, or he’d be off to interview somebody and I would just tag along. When he was working at the Washington Post, I would go into the newsroom all the time. I would wander over to the sports department and steal all of their Milwaukee Brewers AP wire photos they kept in these folders. I would hear stories from my dad’s friends about the stories they were working on. Bob Woodward was the first person to show me a Walkman back in the ‘80s. Being around that showed me this is a profession that’s normal that people I know do and that writing is respected. The people that I love, this matters to them. When I was 13, I tried to start my own sports magazine – it lasted one issue. In high school, I played baseball and was sports editor of the school paper. I became the sports editor at Vandy. But it wasn’t like anyone sat me down and said, “Here are the rules of writing.” They didn’t have a journalism major at Vandy. I was a history major, so it was more by experience and watching that I got most of the lessons.

Reading good writing too. I was lucky and didn’t know it. Reading my father’s writing, I was reading a good writer. The Washington Post was the paper we’d get, so I was reading good journalism there. That influenced me. My parents said I learned to read by reading the back of baseball cards. For me, sports and writing have always been connected.

Q: As a kid, you attended some press conferences with your dad. What was that like?

A: It was interesting because sometimes various politicians would be working the PR. Be nice to the kid of the reporter that’s covering the story. I’d say, “Oh, that’s a really nice guy.” But my dad would say, “Ah, they’re just doing that to try to get me to write something nice about them.” (laughs).

Q: A lot of your books cater to a teen audience. As a writer, how much do you have to adjust your style for a younger readership?

A: A little bit but maybe not as much as some people might expect. The advice I got from my editors was “don’t dumb down the story.” Teenagers are ready for basically anything. I really do the same research that I would do as if I’m writing strictly for adults. I try to write the books in a way adults might not even know it’s going to be marketed more as a young adult book for teens. The books tend to be a little bit shorter. I try to make sure that each chapter has an interesting beginning and a good ending. With younger readers, the main thing is reading stamina, are they going to continue to read this book? You can’t take it for granted that once they get started, they’re going to finish, so I try to build in some tension and cliffhangers to get them to turn the page and keep going. I love to provide a lot of context in my books. What is the place, time, and culture that these characters exist in? It’s good to do that but you can’t drift too far from the main story because you might lose a teen reader. I also like to include a lot of photographs in my book also. Even as an adult, I love pictures in books, but it’s especially important for younger readers. It’s like if they see a page coming up that’s all pictures, it’s like, “All right, I can just keep moving to the next page and I don’t have to read anything.”

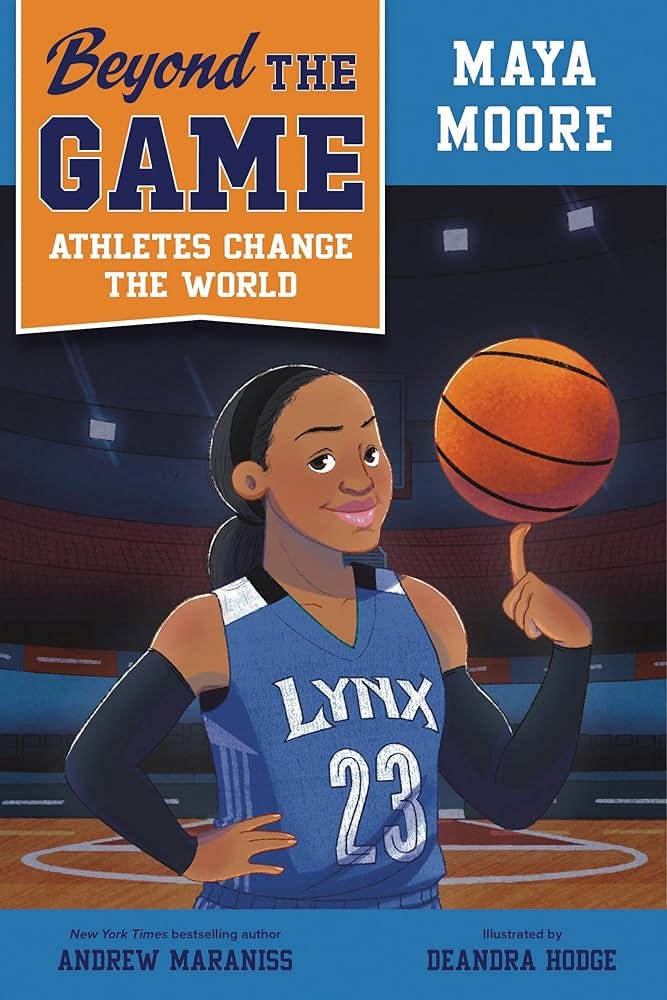

Also, on March 5, I have a new series coming out for first, second and third graders called “Beyond the Game,” which are short, illustrated biographies of athletes that have done something good outside of sports. For those books, yes, it’s a completely different style of writing. These are little kids reading their first chapter book. Those are actually the hardest books I’ve had to write, even though they’re shorter and require less research, just telling the stories in a way that’s entertaining and also educational with the right vocabulary for young kids is a challenge.

Q: It looks like the first two books in “Beyond the Game” are about Maya Moore and LeBron James.

A: Yes, both athletes who’ve done things to help other people. Maya Moore, her quitting the WNBA to help get an innocent man out of prison and LeBron starting his school in Akron, Ohio and refusing to “shut up and dribble” and still speak out on social issues. Those are the first two books in that series. The third book will be on Pat Tillman. The fourth book, I can’t quite say yet because it hasn’t been approved but there will be at least four books in the “Beyond the Game” series.

My next book for teens and adults will be on the first Special Olympics in Chicago in 1968. I’m just getting started with the research and interviews on that project, so look for that one in the future.